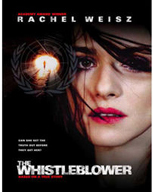

Sexual trafficking. It's hard for people to wrap their minds around the scope of the problem. A new film, The Whistleblower, presents an on the ground retelling of the story of Kathryn Bolkovac (Rachel Weisz), a Nebraskan police officer who became part of the United Nations police team in post-war Bosnia. Hired by Democra, a government contractor that recruited candidates, she uncovered a trafficking operation that reached to the highest echelons of power.

The movie is structured in a style reminiscent of the 1980s Costa-Gavrasnarratives. The dramatization is based on actual events. Some characters have been merged, with names and timelines changed for the sake of a streamlined plot. One of the anchoring characters is Madeleine Rees (Vanessa Redgrave), who was the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Bosnia.

Shot in palettes of blues and browns, the facts are laid out as Bolkovac -- who is of Croatian descent -- takes her belief in "doing her job" into the field. After ten years of experience on the domestic violence beat back home, Bolkovac finds herself up against a web of corrupt players ranging from local police and United Nations peacekeepers, to State Department brass and Democra bigwigs.

Bolkovac discovers that the area's bars and clubs are serving as a front to sites where girls from the Ukraine, Russia, and Eastern Europe have been enslaved. Many of the girls being sold to an international clientele are between 12 and 15 years old.

The story's trajectory follows Bolkovac (who served as a story consultant) from her discovery of trafficking corruption, complicity, and cover-ups through her efforts to report her findings--despite files of evidence disappearing and witness tampering. Death threats are the precursor to her being fired, when she gets too close to the truth. The multilayered cover-up finally sees the light of day when she files a wrongful dismissal case against Democra, and feeds the information from her findings to the British press.

Director Larysa Kondracki spent time with her co-writer in Eastern Europe doing background research. There are two key scenes that speak volumes. One is revelatory, the other is searing. In the former, Bolkovac--and the audience--begin to understand the magnitude of what she is up against as she scrutinizes the first photos and bits of information she had pinned to her office wall. The camera pulls back to show how the original findings have grown exponentially. The latter is an indelible image of one of the girls being raped, tortured and killed in front of the others, as an example of why compliance is the only way to survive.

The Human Rights Watch Film Festival showcased the New York premiere of The Whistleblower in June. HRW has done extensive work documenting post-war abuse in the Balkans. Their website article "Bosnia and Herzegovina: Traffickers Walk Free" gives an overview of the material covered in the movie. In addition, they issued a report in 2002 that breaks down their findings into twelve comprehensive sections.

I interviewed Kondracki by e-mail to get additional insights about her vision and aspirations for the movie. She explained that as a Ukrainian Canadian, the issue of sex trafficking was widely discussed within her community. When she read Bolkovac's book, The Whistleblower: Sex Trafficking, Military Contractors, and One Woman's Fight for Justice, she was overwhelmed by the breadth of the crime of trafficking. She was surprised that a film had not already been made.

What made you decide to do the movie as an indie film? Did you think it would give you more latitude to portray the story as you best saw fit?

To be honest, I didn't see another way. We set out to do it. We spent some time in studios, which was a valuable experience and I think the script was improved when we were there. But ultimately, this was the way that made sense. That's where I have to hand it to the producers. Once we got the project out, we were shooting within nine months.

Do you see the film reaching people about the issue of human trafficking in a way that a news story or article cannot? Are you hoping that the "political thriller" tag will pull people in, which might otherwise be afraid of the subject matter?

Absolutely. Kathy's story is practically a Robert Ludlum novel. Sex, scandal, corruption, governments, international cover-ups. It's something you would usually make up. Our primary goal was to make a good thriller with a great character at the center. Is she going to get the girl? Are they going to get our heroine?

Was it Bolkovac's experience with domestic violence in the United States, combined with how she got a conviction on her first time at bat in Bosnia, that made Madeleine Rees reach out to her?

Yes. That conviction made Kathy really stand out.

How did you decide how far to go with graphically showing the abuse and torture of the trafficked girls?

I wasn't going to make this movie and not be realistic. But I also had no intention of deterring audiences. We tested it several times, and found the right balance. You don't see anything. It's not unlike Silence of the Lambs in a way. It's what's inferred.

How is the United Nations dealing with the film? I understand there was an internal memo that was circulated that advocated a "no comment" policy. Does that suggest that they haven't learned anything from their experience about transparency?

The internal memo left it at the UN being split. But we have learned from sources that they are sticking with a "damage control" policy. I really have no idea what they've learned, and why they aren't seizing the opportunity not only to right these wrongs, but in doing so, to gain some faith from so many cynics that are watching. Show us you want to be the organization you're meant to be. I've written a letter to Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon, and we have offered to screen the film wherever and whenever they want. So far...No Comment.

The internal memo left it at the UN being split. But we have learned from sources that they are sticking with a "damage control" policy. I really have no idea what they've learned, and why they aren't seizing the opportunity not only to right these wrongs, but in doing so, to gain some faith from so many cynics that are watching. Show us you want to be the organization you're meant to be. I've written a letter to Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon, and we have offered to screen the film wherever and whenever they want. So far...No Comment.

cultureID specifically deals with connecting those doing cultural work with political and social intent/content with audiences. How do you see The Whistleblower within this context?

I genuinely believe that films have one of the loudest voices. And I believe that if we can get this story into public discourse, the State Department and the United Nations will be embarrassed. Hopefully, enough to do something. Look at Guantanamo, extraordinary renditions...I'm not saying that's done with, but at least they aren't snatching people in plain sight out of airports anymore. Same thing here. U.S. tax dollars should not be going to the buying and selling of girls. Period. There's no grey area to that.

I genuinely believe that films have one of the loudest voices. And I believe that if we can get this story into public discourse, the State Department and the United Nations will be embarrassed. Hopefully, enough to do something. Look at Guantanamo, extraordinary renditions...I'm not saying that's done with, but at least they aren't snatching people in plain sight out of airports anymore. Same thing here. U.S. tax dollars should not be going to the buying and selling of girls. Period. There's no grey area to that.

This article originally appeared on the site cultureID..

Follow Marcia G. Yerman on Twitter: www.twitter.com/mgyerman